In late March, OpenAI made it possible to “Ghiblify” yourself — using its newest version of ChatGPT, with updated image generation capabilities, users could easily create images in the style of Studio Ghibli, the animation studio behind works like My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke. Very quickly, users began generating Ghibli style images on a large scale. Sam Altman, adopting a Ghibli avatar himself, noted that ChatGPT had added one million new users in one hour, in no small part due to the virality of the Ghibli phenomenon.

The backlash against OpenAI was also quick to develop, with some upset fans hoping that “everyone” would be sued for appropriating the Ghibli style. Professor Ed Lee, writing about the issue in his blog ChatGPTIsEatingtheWorld, noted that courting this kind of controversy may be part of a larger pattern of behavior for Altman — last year, he created a similar controversy around the use of an AI voice very reminiscent of that of Scarlett Johansson, who voiced an AI in the 2013 film Her.

Regardless of Altman’s specific motivations, the Ghibli phenomenon is a good illustration of an issue that is top of mind for those of us watching developments in AI: when do copyright laws consider an AI-generated output to infringe on an existing work? More narrowly here, does U.S. copyright protect the Ghibli style, such that OpenAI may be courting legal trouble with this type of use?

Why copyright (often) does not and should not protect style

There are some really good reasons why copyright law should not protect style. Imagine that you are a filmmaker working with a major studio and you develop a unique and successful visual style over the course of several movies. You’ve transferred your rights to those movies to the studio and then you decide to make movies with a rival studio. Suppose we live in a world where the style you developed and employed is copyrightable on its own. The first studio, holding copyright in your style, might prevent you from employing that visual style in future works. Your future output would then either be substantially constrained or you would forever be required to seek permission for new uses of the style you worked hard to develop.

Imagine that you are creating in any arena, and style is viewed as copyrightable on its own. Similar issues to the ones described above would arise: a book publisher might prevent an author from taking their unique writing style to a rival publisher; a musician might be forced to choose between continuing to make music their way and moving to another label. The styles of painters, book illustrators, and comic book artists could all be similarly captured if style were copyrightable.

One can also imagine other problems arising: a gold-rush mentality would likely pervade creative fields, creating an urgency to identify new styles and monopolize them as quickly as possible. Correspondingly, there would likely be a massive chilling effect among creators, with many fearing the consequences of treading too closely to the style of other artists and authors. Broad categories of creativity would quickly be enclosed. Such copyright laws would serve to stifle creativity instead of fueling it

Fortunately, we largely don’t live in a world where style is protected in this way. We don’t talk about a single impressionist or a lone surrealist, there is not only one hip hop musician or one fantasy+romance+dragons author. We talk about these movements and genres across many artists. We talk about schools of art and periods of literature, where the stylistic choices of creative people of the day inform one another and flow quite freely.

How does style remain largely uncopyrightable?

There are a number of reasons why style is largely uncopyrightable and would render significant portions of Studio Ghibli style unprotectable (when courts decide infringement cases, they filter out unprotectable elements from copyrightable expression through a variety of methods; the Abstraction-Filtration-Comparison test for software is one such method). Several of these reasons are foundational principles of copyright law that may be familiar to most of you:

Ideas are not protectable: Copyright protection does not extend to ideas (17 U.S.C. § 102(b)) When the style of a work does not rise beyond the level of an unprotectable idea, it is not copyrightable. For example, the US Copyright Office refused to register this bridal headband, finding that the headband’s “combination, selection, and arrangement of elements is insufficiently creative to warrant copyright protection.”

Scenes à Faire: This doctrine holds that elements standard or indispensable to a particular genre, topic, or setting (“scenes which must be done”) are not protectable. Clandestine meetings in spy thrillers, shootouts in Westerns, stock characters in sitcoms, or common algorithms in software are good examples. Stylistic choices often fall under this umbrella — the gritty realism expected in a crime drama, the bright colors common in children’s books, the large and expressive features found in cartoons, the specific instrumentation defining a musical genre. Very frequently, style is widely recognized as part of the shared language of the form.

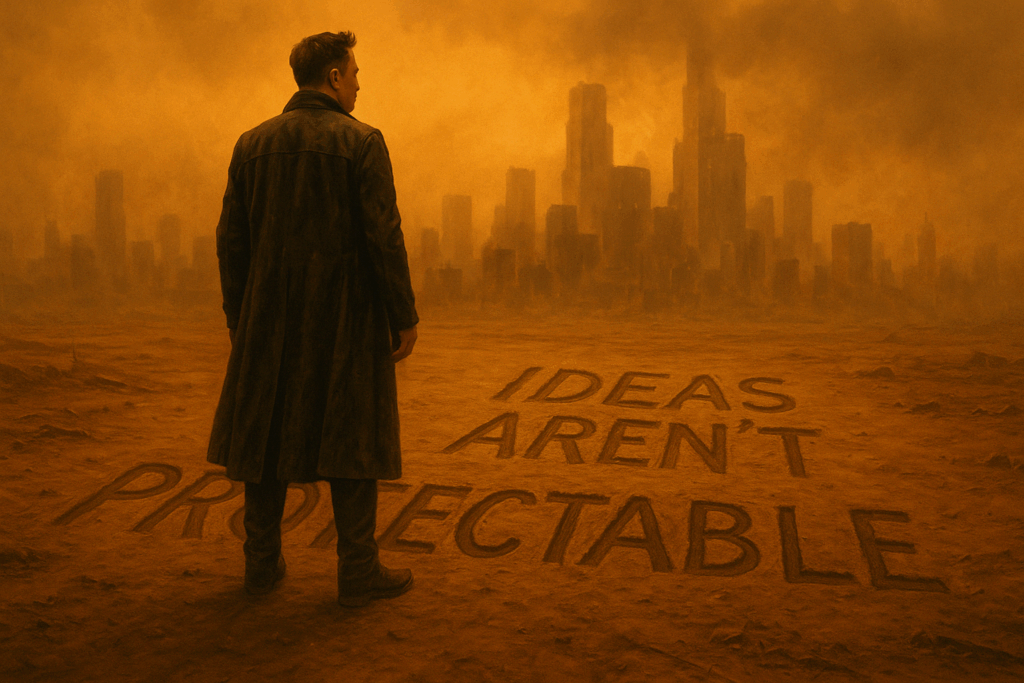

Merger Doctrine: When an idea can only be expressed in a very limited number of ways, the expression is said to “merge” with the idea, rendering it unprotectable. If protecting the expression would effectively grant a monopoly over the underlying idea, copyright steps back. For example, stylistically, a post-apocalyptic dystopia will almost never resemble a verdant valley – when encountering stylistic renderings of this theme, one would expect muted sunlight, barren earth, and other signs of decay and destruction. Expressions that match up with that expectation, standing alone, generally should not be protectable.

Fair Use: Fair use (17 U.S.C. § 107) allows use of copyrighted material without permission from rights holders. Transformative uses of works—those that add something new, altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message—are frequently especially favored under fair use. We see fair use informed borrowing in all creative fields, and its scope encompasses the borrowing of styles from other creators, when those styles are part of otherwise protectable expression.

And yet… At times, copyright law intersects with style

Despite the doctrines detailed above and the general understanding that copyright does not protect style alone, the reality on the ground can be messier. Courts, comparing specific works, sometimes issue rulings where the copyrightability of style (not standing in isolation, but as a substantial weight considered in the expression of the work) is heavily implicated in infringement findings. This often happens when style is deeply intertwined with other, more clearly protectable elements like specific characters or the overall “total concept and feel” of the works.

Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. (663 F. Supp. 706 (S.D.N.Y. 1987)) is a classic example. Artist Saul Steinberg sued Columbia Pictures, alleging that the promotional poster for the movie Moscow on the Hudson infringed the copyright of his famous New Yorker cover illustration, “View of the World from 9th Avenue.” Both images feature a bird’s-eye, distorted perspective of New York City looking west, with Manhattan dominating the foreground and the rest of the world receding rapidly into a narrow strip at the top. Steinberg’s style—whimsical, with distinctive lettering and linework—was central to the cover’s identity.

The court found infringement. While acknowledging that ideas (like a map showing a New Yorker’s worldview) aren’t protectable, the court stated: “Even at first glance, one can see the striking stylistic relationship between the posters, and since style is one ingredient of “expression,” this relationship is significant.”

The court noted the similar “whimsical” style, the “errors and anomalies of Steinberg’s shadows and streetlight” and the specific choices in perspective and layout. While framed as protecting Steinberg’s specific expression, the ruling undeniably gave significant weight to his unique artistic style as a key component of that expression. Did Columbia copy the idea of a parochial map, or the specific stylized expression of that idea? The court leaned towards the latter, with Steinberg’s style deeply woven into its discussion of the protected expression.

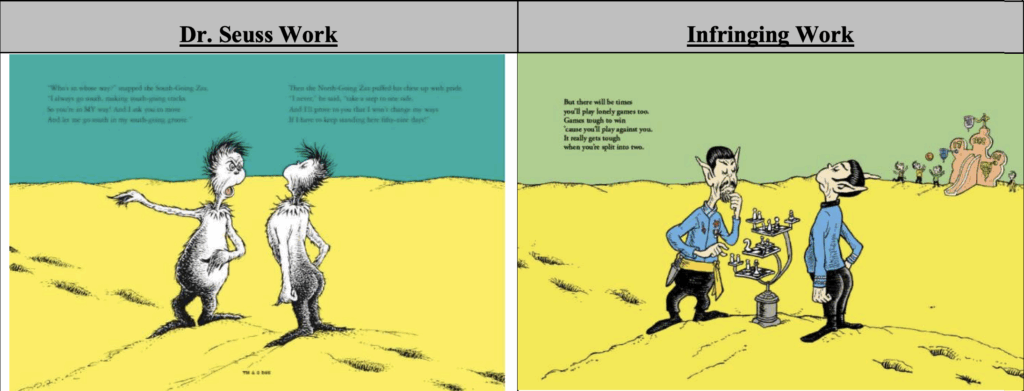

Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. ComicMix LLC (983 F.3d 443 (9th Cir. 2020)) provides another, perhaps more complex example. ComicMix created Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go!, a book mashup combining elements of Star Trek with the distinct artistic and literary style of Dr. Seuss’s Oh, the Places You’ll Go! and other Seuss works. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ultimately rejected the argument that the new work was a fair use and found infringement.

In reading through both the plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment (“Defendants’ intent was always to steal the familiar illustration style and prose/poetry style of well-known children’s books to make their Star Trek story more appealing and salable.”) and the court’s opinion, it is hard to escape the conclusion that Seuss’s style is a substantial part of both what the plaintiff sought to protect and the court viewed as protectable. (“ComicMix captured the placements and poses of the characters, as well as every red hatch mark arching over the handholding characters.”).

While one might argue that some of the focus on style was more in service of the plaintiff’s trademark related claims, the court makes little attempt to unpack what precisely Seuss’s copyright protects and what it does not protect. This may be partly due to the defendant’s choice to focus on other arguments, but it also fits the pattern of the larger issue – that style can be incredibly difficult to ignore or extract from considerations related to protectable expression.

Alcon Entertainment, LLC v. Tesla, Inc. (Case No. 2:24-cv-9033-GW-RAOX, C.D. Cal.) offers a current glimpse into these tensions, one involving Artificial Intelligence. Alcon, rights holder in Blade Runner 2049, sued Tesla, Elon Musk, and Warner Bros. over a promotional event for Tesla’s “cybercab.” The event opened with an AI-generated image displayed for 11 seconds, showing a male figure in a duster coat, seen from behind in silhouette, surveying orange-lit urban ruins, with the words “Not This” superimposed. Musk’s voiceover mentioned loving “Blade Runner” but not wanting “that future,” referencing the character’s “duster” and the “bleak apocalypse”.

Alcon argued this infringed its copyright in BR2049 and included not just the distinctive visuals of the character “K” (duster-clad silhouette in orange-lit ruins ) and the iconic “Las Vegas Sequence”, but also the film’s mood (“Anxiety, Fear and Urgency” ), setting (post-apocalyptic ruins bathed in orange light ), and theme (“Urgent Human-AI Decision Point” expressed visually ). Alcon contended that even still images from the film are potent vehicles for evoking these other protected elements and that the AI-generated image was created by feeding BR2049 elements into an AI generator. They essentially argued that the defendants copied the evocative style and atmosphere that defined key parts of their film.

In a tentative ruling on motions to dismiss, the court explored these claims. So far, it has allowed the direct infringement claim against Tesla/Musk to proceed based on the “literal copying via AI input” theory (since how the image was made was within defendants’ knowledge ). While many of us view the Tesla image as filled with unprotectable elements and that the claim ultimately should not survive summary judgment, this case demonstrates just how far stylistic similarities can take a plaintiff—for now, it seems that the claim will survive a motion to dismiss, drawing the litigation out further, and running up the cost of litigation substantially.

Conclusion/Where does this leave us?

It is clear that Artificial Intelligence has the potential to bring enormous changes to our culture, our labor force, our art forms, to science, to literature – the list is long and growing. The Ghiblification trend is a hint at a future challenge facing our copyright laws – one informed in part by its scale and and also by its fairly high quality.

Five years ago, there may have been a trending meme that used a series of images or limited portion of an in copyright work. But, even if shared broadly, the viral meme would typically not be monumental in its scale and reach. In Ghibli, we’re beginning to see a change – it’s not a single image meme that is shared broadly, but a tsunami of images and uses that will often defy simple categorization. Artificial Intelligence will facilitate widespread, incredibly high quality (rivaling the quality of today’s highly paid artists/graphic designers), and very easy to produce works that will put considerable pressure on our sense of what is a permissible use of another artist’s work, and precisely where the lines should be.

The cases detailed above illustrate some of the contours of the tension that already exists around questions of copyright and style. While we may wish to confidently claim that copyright never protects mere style, the line between unprotectable style and protectable expression can be incredibly thin bordering on nonexistent, especially when dealing with highly distinctive works or specific combinations of elements. Add in high profile and high dollar value uses of an artist’s style, and you have a recipe for litigation or threats of litigation, even if ultimately meritless. Courts will continue to grapple with separating the ‘idea’ (a dystopian future, a children’s story about life choices, a parochial worldview) from the ‘expression’ (the specific visuals, characters, text, and feel that bring it to life). Sometimes it will take them time to get it right.

While it might be tempting to want to protect the Ghibli style, we should remain mindful of the core purpose of copyright: to promote creativity for the public good (“The immediate effect of our copyright law is to secure a fair return for an `author’s’ creative labor. But the ultimate aim is, by this incentive, to stimulate artistic creativity for the general public good.”) Overzealous protection of style risks enclosing the common building blocks creators rely on, preventing one creator from building on the style of another.

We can think of it on an even smaller scale – Studio Ghibli was founded in 1985, over twenty years after Hayao Miyazaki had started working in animation. Imagine if Miyazaki had not been able to carry the style he had cultivated during those twenty plus years of previous work into his new studio. If style itself becomes too easily monopolized, we could easily find ourselves in an impoverished creative landscape, as barren and unwelcoming as the red clay earth of Blade Runner’s dystopian vision.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.