EDIT: On Sunday evening, Judge Alsup granted the motion for a hearing on Monday, September 8th, but expressed disappointment over lack of details, mostly on the issues I point out below. Sounds like he is unlikely to approve without those issues resolved.

On Friday, both sides in the Bartz v. Anthropic lawsuit filed motions for the court to consider regarding preliminary approval of a settlement in the class action copyright infringement lawsuit filed against Anthropic last year by three book authors.

There has been a lot of reporting on the case. Some of that reporting has been quite good, but a lot has fallen short of the mark. In particular, I think three things are important points to make clear about what this settlement isn’t:

- This settlement isn’t really about AI training. The court, in June, had already concluded that Anthropic’s LLM training was a fair use, and it also determined that Anthropic could legally scan books. Nothing in this decision displaces that decision (which I think is a good thing). Instead, the case has come to focus on Anthropic’s downloading and storage of files from LibGen and PiLiMi.

- The settlement isn’t a settlement with “authors.” Or at least not just authors. The moment Judge Alsup defined and certified the class in this case to include any rightsholder with an interest in the exclusive copyright right of reproduction in a LibGen/PilLiMi book downloaded by Anthropic, this case became at least as important for publishers as authors.

- The settlement isn’t far-reaching. While the payment is record-setting for a copyright class action ($1.5 billion), the settlement terms are pretty narrow in scope. Anthropic simply gets a release from liability for past conduct – namely, use of the LibGen and PiLiMi datasets. It is therefore unlike the proposed settlement in the Google Books Settlement that would have created a novel licensing scheme for a wide variety of future uses (something that I worried a settlement could result in, and am relieved it is not).

I’m sympathetic to both sides wanting to settle this case – Anthropic faces incredible liability if things were to go the wrong way for it. And for the plaintiff’s side, it remains far from clear that Judge Alsup’s theory of the case — namely, that downloading and storage of copies should be treated distinctly from the actual training, which he upheld as fair use — would hold up on appeal. Overall, I think the terms are pretty reasonable for what they accomplish for each side, but they also do very little for authors who have very different concerns than the primarily monetary ones put forth by the class representatives (see, e.g., this fantastic piece by Dan Cohen, Authors Alliance board member and probable class member in this suit).

The settlement raises lots of questions. This post is the first of what I’m sure will be more to come. Right now, I want to focus on one pretty simple question that I think most of us are curious about – who would get paid?

Below, I reference Anthropic’s motion and the Plaintiffs’ identical (I think) motion asking the court to give preliminary approval to the proposed settlement. Each explains the background and legal rationale for why the court should accept the settlement, as well as the actual proposed settlement, here.

How much will each book rightsholder get paid?

It’s been widely reported that the settlement is for $1.5 billion, and that the suit covers approximately 500,000 books. But, we don’t actually know yet how much payments to rightsholders would be. Here’s why:

The settlement is structured around a “Works List” that is made up of the books that are covered by the class definition – that is, books that:

- Were downloaded by Anthropic from LibGen or PiLiMi

- Have an ISBN or ASIN

- Were registered with the US Copyright Office before being downloaded by Anthropic (which, according to the proposed settlement, occurred on August 10, 2022).

Anthropic, in its motion, explains that the Plaintiffs served on it a list of the approximately 465,000 works which Plaintiffs presently believe satisfy the criteria for inclusion on the Works List. Anthropic has additionally promised to pay $3,000 more for each book that is added to the list if it ends up exceeding 500,000, and has further told the court that the parties will confer on the list and submit a copy to the court with any changes by October 10, 2025.

Right now, we know that each book would be treated equally – (Settlement p.9 stated that settlement funds will be “distributed on an equal-per-work basis, after deduction of any fees, expenses, or service awards approved by the Court.” We also know that any unpaid funds–e.g., should some rightsholders not make a claim–will be distributed on a “pro-rata basis.” (Settlement p.8).

I think it is fair to say that it is unlikely that rightsholders for all of the books will come forward, so it is entirely possible that the Settlment Fund could be split amongst some group of rightsholders representing fewer than 500,000 books, thereby increasing the total per book payout. Assuming the settlement is approved, will have to wait and see how many come forward to claim funds or opt out.

All that said, what we really don’t know is how much each individual author or rightsholder will get. As I mentioned above, the case changed its tenor when Judge Alsup approved a class that is defined to include “All beneficial or legal copyright owners of the exclusive right to reproduce copies of any book in the versions of LibGenor PiLiMi downloaded by Anthropic” that fit within the Work List defined above.

In some instances, who owns the “exclusive right to reproduce” is quite murky –e.g., under a publishing contract that gives the publisher the “right to publish” the book in certain formats. In others–e.g., many academic publishing contracts where authors assign all rights to the publisher–the issue is relatively clear. And in some other cases, it could be the case that an author–e.g., authors of a multi-chapter book–isn’t the legal or beneficial owner at all (since they assign all rights and get no royalties) and would be excluded from the class, while the publisher would be presumably entitled to 100%.

How to handle competing claims to the same work is not spelled out in the actual settlement. Instead, as the settlement (p.11) explains, “Each Class Member with an Approved Claim shall be entitled to a Settlement Payment allocated in accordance with the forthcoming ‘Plan of Allocation.” (more on this below).

We don’t yet know much about what makes up the works list to know which books are more likely to be ones where authors hold the relevant rights versus publishers. Based on the analysis we did ourselves of the LibGen dataset and what we know more generally about the contents of LibGen and PiLiMi, it seems pretty clear to me that many of these books are likely to be nonfiction scholarly works and textbooks published by some of the largest academic publishers, along with large numbers of fiction works from the “Big Five” trade book publishers. Payments to those publishers under this settlement are likely to be substantial.

How Much Of the Settlement Will Go to Rightsholders?

The $1.5 billion needs to cover more than just payments to rightsholders, and there are other substantial costs that could make payouts come in below the benchmark $3,000 per work that is widely reported. The Settlement explains that it will be used to cover the following:

- All Settlement Payments to Class Members with Approved Claims,

- Settlement Administration Expenses,

- Any service award to each Class Representative approved by the Court

- Any Fee Award to be decided by the Court

- Fees for the services of a Special Master (a court-appointed neutral party to handle disputes about claims. More on this below.

- Fees for the services of industry expert members of the working group, including the Hon. Layn Phillips, to the extent any are required.

Some of these costs could be substantial. First, the biggest is the fee for the Plaintiff’s lawyers. We know from Anthropic’s and Class Counsel’s motion that Class Counsel intends to seek a Fee Award of “an amount not exceeding 25% of the Settlement Fund, the benchmark percentage for a reasonable fee award in the Ninth Circuit.” If the plaintiff’s lawyers do end up seeking 25% (a quick look at previous class action litigation with this firm indicates they have sought the full amount they were able to), those fees would come in at $375 million. The court, under Rule 23(h), would have to approve such a payment and ensure it is reasonable, but as the Plaintiffs note, 25% falls within the range of reasonable possibility based on 9th Circuit law.

Second, settlement fee administration expenses will cost something – nowhere near the costs of the attorneys’ fees, but likely several million dollars, at least.

Third, a “service fee” award to the class representatives. This would be modest in the grand scheme of the settlement– the settlement proposes $50,000 per class representative, which strikes me as reasonable given the time they had to devote to the case so far.

Third, fees for the Special Master to resolve disputes amongst class members– likely to be a minimal cost.

And finally, a fee to “industry experts of the working group.” This is an interesting piece, though whatever fees are paid here are unlikely to make much of a dent in the overall Settlement Fund.

How substantial these fees will be, we’re not sure. But it’s easy to see that about a quarter to a third of this settlement is being used up before rightsholders see anything.

Who decides how funds are split amongst rights holders of the same book?

The industry working group, paid out of the Settlement Fund, is one of the more interesting features of the Settlement. As we noted in our amicus brief opposing class certification, there are likely to be disputes between various owners with a claim over a work due to the way publishing contracts allocate rights. For example, beneficial owners (typically authors) may disagree with legal owners (typically publishers) about how to split any per-work payment. Or, there may be disputes over who controls the rights at issue at all, given variations in underlying publishing contracts. Given the size–currently maxing out at rightsholders of 465,000 books, if all those rightsholders show up to argue for their rights, this may not be as challenging as if there were millions in the class. But it still could pose a significant challenge.

To address this, Anthropic in its motion, explains that “Class Counsel has assembled an Author-Publisher Working Group (APWG) to provide advice and proposals for how to efficiently address intra-work distributions that may arise during the claims administration process, including the formulation of a claims form that provides any information necessary to address intra-work allocation, adjustments to the proposed form of notice, and process and procedures designed to minimize the administrative burden of claims administration.”

The APWG will exist to “advise Class Counsel on the claims process, the contents of a Claim Form, and adjustments to the relevant sections of the form of Class Notice for the purpose of fairly, equitably, and efficiently addressing situations where there are multiple Claimants submitting claims for a particular work on the Works List. We know a few more details.” (Settlement p. 26).

We don’t really know who is in this group, except that “it will be led by two industry experts, Authors Guild CEO Mary Rasenberger and Association of American Publishers CEO Maria Pallante, and will also be supervised by the Hon. Layn R. Phillips (Ret.).” Given what I suspect is the makeup of the works list and class, including many nonfiction scholarly works, I really hope it also includes some representatives who can speak for the likely large number of authors and publishers who are not well represented or aligned with the Authors Guild or AAP.

The group will apparently need to do quick work. It is expected to send its recommendations to Class Counsel by September 30, and Class Counsel then plans to submit some or all of those recommendations “for the Court’s approval by October 10, 2025 [including] any Plan of Allocation, Claim Form, or adjustment resulting from the Working Group.” (Settlement p. 26).

I think one of the most important documents to be on the lookout for is this “Plan of Allocation,” which sounds like it will, in large part, determine the method through which settlement funds will be split between authors and publishers.

What comes next?

The parties have asked the court for a hearing on September 8th (tomorrow) at noon Pacific to hear their motion for preliminary approval. I hesitate to say where this will go from there – the court in this case has been quite assertive (e.g., inventing its own class definition that no one in the case actually asked for). But the court has a track record in this case of moving fast.

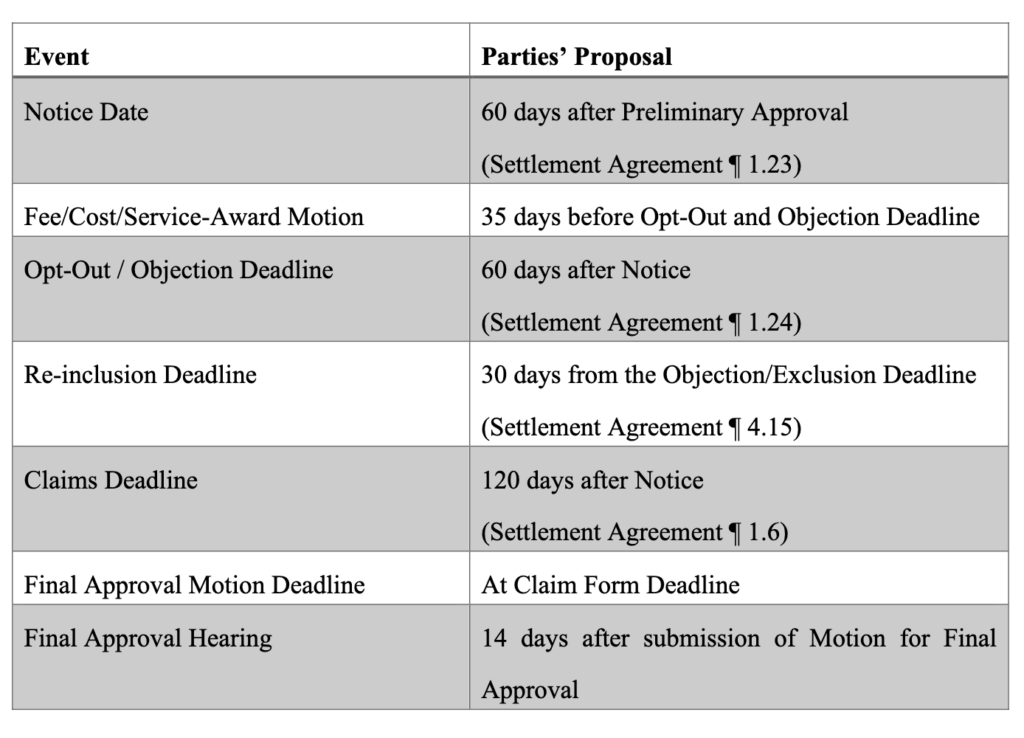

From there, the timeline is largely dependent on when the court grants preliminary approval, as indicated in this chart:

Conclusion

There are lots of other interesting parts to this proposed settlement not addressed in this post – particularly how they plan to actually reach authors and right-holders, how disputes among competing claims will be resolved, and how rightholders can opt out (and what happens if many do). More on those later.

Perhaps the most important takeaway from all this is what this settlement is not: this settlement doesn’t establish new precedents for AI training or create ongoing licensing obligations for Anthropic. It simply resolves liability for past conduct involving the LibGen and PiLiMi datasets, leaving the broader legal landscape around AI training largely unchanged. Judge Alsup’s earlier ruling that LLM training constitutes fair use remains intact and continues to provide important guidance for the industry.

The real test will come in the implementation details—particularly the Plan of Allocation that emerges from the Author-Publisher Working Group. How that plan addresses the complex web of publishing rights and competing claims will likely determine whether this settlement is remembered as a fair resolution or as a windfall primarily benefiting large publishers.

For now, we’ll have to wait and see how the preliminary approval hearing unfolds on September 8th and whether the court’s characteristically assertive approach in this case leads to any surprises in the settlement’s final form.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Anthropic’s AI Lawsuit Settlement Could Not Go By means of, However It Exposes A Reality About Copyright - The TechNews

Pingback: Anthropic’s AI lawsuit settlement may not go through, but it exposes a truth about copyright – Walled Culture

Pingback: Why 'Fair Use' Cannot Justify Piracy in AI Training Cases

Pingback: Updates in the world of AI: September 2025 – Pratt Institute Center for Teaching and Learning

This breakdown is super helpful! Its clear theyre trying to sort out who gets paid, but the complexity around rights ownership and fees is wild. Definitely makes you wonder about the final payout per book.

Pingback: About That Anthropic Settlement – Darker Realities