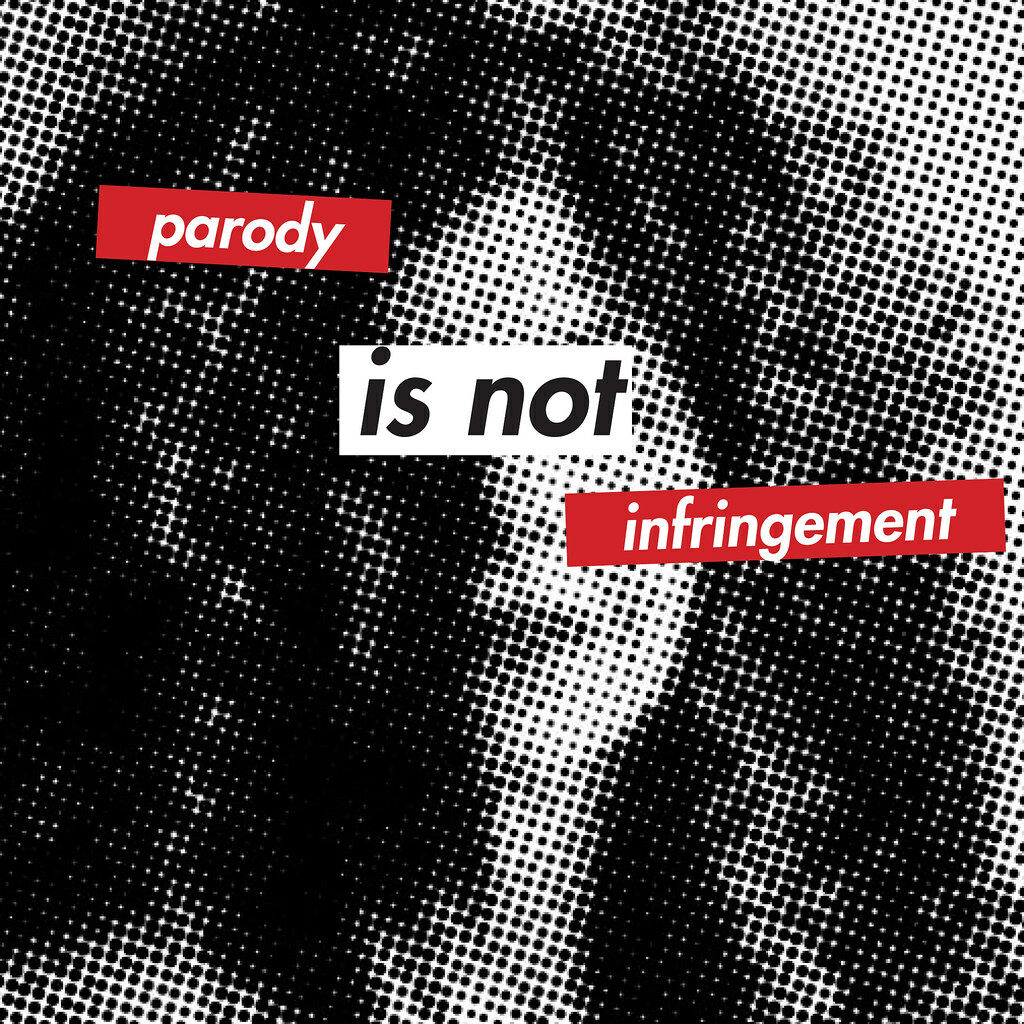

Fair use is one of the more dynamic topics in copyright law lately—the Supreme Court has issued decisions or agreed to hear cases in two separate fair use cases that could affect how authors can rely on fair use just within the past year and a half. Fair use is also a topic Authors Alliance discusses a lot on this blog and elsewhere—we care about fair use so much that we wrote a book on it! While our guide focuses on fair use for nonfiction writers, fiction authors can and do rely on fair use to create new creative works of authorship. One of the clearest examples of fair use in the realm of fiction is parody (a topic we previously discussed in our 2020 series on fair use for fiction authors). At the most basic level, a parody is defined as “a literary or musical work in which the style of an author or work is closely imitated for comic effect or in ridicule.” In today’s post, we will contextualize parodies within copyright and offer some thoughts on how law and practice surrounding parody might affect authors of parodies and authors more generally.

Parody at the Supreme Court

The landmark Supreme Court decision that proposed a framework for a use’s “transformativeness” which is still relied upon today, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, was itself a case about parody. In the case, the rap group 2 Live Crew recorded and released a song entitled “Pretty Woman.” The song drew from “Oh, Pretty Woman,” a rock ballad by Roy Orbinson and William Dees which was featured in the film Pretty Woman. After reusing a familiar line from the song, the 2 Live Crew song “degenerates into a play on words, substituting predictable lyrics with shocking ones.” The song “juxtaposes the romantic musings of a man whose fantasy comes true, with degrading taunts, a bawdy demand for sex, and a sigh of relief from paternal responsibility.” The Court interpreted this change “as a comment on the naiveté of the original of an earlier day, as a rejection of its sentiment that ignores the ugliness of street life and the debasement that it signifies.” While many remember Campbell for the concept of transformativeness that it established as part of the test for fair use, it also shows the strong legal protection for parodies.

Parodies and Artistic Judgments

One issue that sometimes arises when an author defends their use of another’s work as a fair use parody is the question of whether it is a parody at all. Courts require more than claims from the author that their work is a parody in order to consider it as such. The question of whether the apparent parody uses the first work for a different purpose, or in a way that is transformative, or merely reuses existing material to unfairly benefit from that creative output, involves some artistic judgment by a court. While courts have, in different ways, resisted being slotted into the role of art critic, some judgment as to a work’s “parodic character” is inevitable.

The recent fair use case, TCA v. McCollum, is an illustrative example of this problem. The case concerned the use of a portion of the comedic routine “Who’s on First,” written by Bud Abbott and Lou Costello, in an original play entitled Hand to God, described as an “irreverent puppet comedy” about “a possessed Christian-ministry [sock] puppet.” While the play was not described as a parody, it did arguably use the comedic routine for comedic effect or ridicule, making it at the very least “parody-like.” In Hand to God, “Who’s on First” takes place as a conversation between the protagonist and Tyrone, a sock puppet worn on the character’s hand. The actor performs both roles, using different voices for the character and the sock puppet. In 2015, a district court found the use of the routine in the play to be “highly transformative,” because “[w]hereas the original Routine involved two actors whose performance falls in the vaudeville genre, Hand to God has only one actor performing the Routine in order to illustrate a larger point.” It explained that “[t]he contrast between [the character’s] seemingly soft-spoken personality and the actual outrageousness of his inner nature, which he expresses through the sock puppet, is, among other things, a darkly comedic critique of the social norms governing a small town in the Bible Belt.”

But the next year, the Second Circuit reversed the district court’s decision, finding that the use of “Who’s on First?” in Hand to God was not transformative or a fair use. The court argued that neither the playwright or the district court had explained how the use of “Who’s on First?” specifically served the “darkly comedic” aim of the play. The court added that its conclusion was bolstered by the fact that the playwright presented a portion of the routine “almost verbatim,” apparently ignoring the fact that verbatim copying can be fair use in some instances. In the view of the Second Circuit, the use of the routine did not “add something new” to “Who’s on First?” with “new expression, meaning, or message.” It is difficult to square this with the astute observations of the district court regarding the creative use of “Who’s on First” in Hand to God, and begs the question of how much artistic judgments are involved when judges decide whether a work is transformative or parodic in character.

Parody in Practice

While the fair use doctrine provides strong legal protection for parodies, in practice, authors might still be cautious about whether and how they create parodies of literary works. The possibility of facing a lawsuit related to a new book is daunting, even when those lawsuits are entirely unsuccessful. The cost of defending a copyright infringement suit can be very high, and authors are already strapped for time and resources they need to create new works of authorship. This threat of copyright liability can lead some authors and other creators to be cautious about creating parodies. For example, there has recently been news of an upcoming horror film parody of Winnie-the-Pooh involving live action actors, entitled Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey. This work arguably fits squarely within the definition of parody, turning Pooh and Piglet from lovable, naive animated characters into gruesome killers portrayed by actors. Yet the filmmaker waited until Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne entered the public domain before creating the film. Moreover, the filmmaker took additional precautions to avoid antagonizing the Milne estate or Disney, who owns copyrights in the character as presented in Disney’s Winnie-the-Pooh films and movies. The filmmaker made sure to pattern the character designs off the drawings in Milne’s book rather than the Disney TV show or films, and even omitted characters like Tigger who did not appear until Milne’s later The House at Pooh Corner, which has not yet entered the public domain.

Parodies and the law around them are an important topic for authors who care about fair use. Fiction authors may be inspired to create new parodies, and nonfiction authors too can take lessons from the laws around parody as to transformativeness and practical caution, even when the law is on one’s side.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.