Earlier this month, we wrote about the recent Ninth Circuit decision in Sicre de Fontbrune v. Wofsy—a case about whether U.S. Courts should enforce foreign copyright judgments when the challenged use would likely be a fair use if the case were brought in the United States.

The good news from Sicre de Fontbrune (at least for U.S. authors) was that the Ninth Circuit seemed to agree that fair use is an important enough matter of public policy to at least deserve further assessment before enforcing a foreign judgment, though it didn’t answer the issue definitively. Although the U.S. is not totally unique in how it approaches fair use, fair use is a distinctive and important part of U.S. public policy, and courts have repeatedly emphasized how it supports core free speech rights as embodied in the First Amendment. So, we think it makes sense that courts should give special attention to fair use and conduct a thorough analysis when U.S. authors have relied on that right.

But unfortunately, when the Ninth Circuit conducted its own fair use assessment, it gave Wofsy’s fair use assertion anything but special attention, conducting a more cursory analysis than the doctrine requires. We see two grave errors in the Ninth Circuit’s decision.

So what did the Ninth Circuit get wrong?

First, some basic facts from the case: Wofsy (the defendant) got permission from the Picasso estate to publish what has now become a standard Picasso reference work, The Picasso Project. The Picasso Project documents Picasso’s greatest works and incorporates substantial reference information. Wofsy reused a number of images of Picasso paintings from an earlier, larger work known as the Zervos Catalogue, in which Sicre De Fontbrune bought rights to in the late 1970s. The Zervos Catalogue is a 33-volume work with over 16,000 images of Picasso’s art, produced with cooperation from Picasso and his estate from 1932-1979. The Zervos Catalogue, which does not contain the same reference information as The Picasso Project, is now out of print and selling on the used market for upwards of $20,000 for all 33 volumes. The Picasso Project is 28 volumes, each of which can be purchased individually for $150 directly from Wofsy (or $4,200 for the whole set).

Sicre de Fontbrune originally sued Wofsy in French court in the mid-1990s when he discovered copies of The Picasso Project for sale in a French bookstore. According to the Ninth Circuit Court’s retelling of the French case, The Picasso Project reused some 1,400 images from the Zervos Catalogue. The court explained that Sicre de Fontbrune’s claim was not that Wofsy infringed Picasso’s copyrights (remember, he had permission from the Picasso estate), but that Wofsy had infringed Sicre de Fontbrune’s rights in the photographs that it had procured of Picasso’s art and published in the Zervos Catalogue.

The district court, in its own abbreviated fair use analysis, concluded that the use was fair, but the Ninth Circuit reversed. You can read the Ninth Circuit’s fair use reasoning here.

The most significant and concerning error in the Ninth Circuit’s opinion is that it didn’t actually evaluate any of the individual photographs in which Sicre de Fontbrune claimed his rights were infringed. The second factor in fair use analysis requires courts to assess the “nature and character” of the underlying photographs. In the words of another Ninth Circuit opinion, the second fair use factor “recognizes that creative works are ‘closer to the core of intended copyright protection’ than informational and functional works, ‘with the consequence that fair use is more difficult to establish when the former works are copied.’”

This factor is particularly important in this case because limits on the scope of copyright protection are one of the other ways that copyright law avoids restricting First Amendment protected speech. As the Supreme Court has explained, “First Amendment protections [are] . . . embodied in the Copyright Act’s distinction between copyrightable expression and uncopyrightable facts and ideas, and the latitude for scholarship and comment traditionally afforded by fair use.” Those limits provide breathing room for the public to freely use underlying ideas and concepts in copyrighted works, while preventing others from locking up that underlying expression from further reuse without adding anything creative or new.

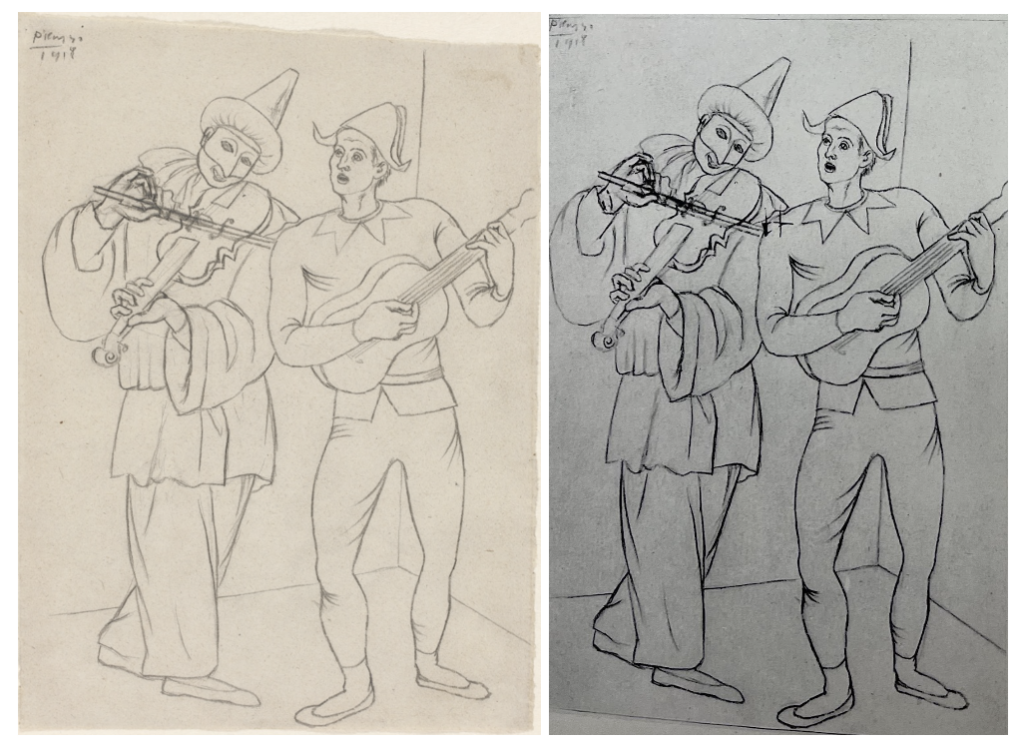

In this case, the defendants didn’t argue (and the court didn’t consider) that the photographs may not be protectable under U.S. law, but the court should have considered the creativity of these photographs more thoroughly as part of its fair use assessment. Instead, the panel merely recited the adage that “photos are generally viewed as creative” and then accepted without question the judgment of the French court regarding whether the photographs could be protected by copyright, using French legal standards to judge creativity, that the photos have “creative elements.” There is nothing to suggest that the panel (or the district court) ever even looked at a copy of the pictures.

While it is true that some photographs can be highly original and creative, the photos in this case are mere photographic representations of other works, exhibiting almost no creativity (a “modicum” of which is required for a work to be protected by copyright in the U.S.). Unfortunately, given the sparse briefing on the fair use issue below and lack of argument from the plaintiffs on fair use, the court never had the opportunity to really look into the creativity issue. At a minimum, the Ninth Circuit should have sent this issue back down to the district court for it to make a judgment for itself. If either court had looked at these photos, it seems obvious to us that the minimal creativity they exhibit would have resulted in the second fair use factor strongly favoring Wofsy’s use.

The other major mistake the court made was to not meaningfully evaluate the “purpose and character” and transformative nature of Wofsy’s use under the first fair use factor, one of the most important factors in fair use analysis. The Ninth Circuit rejected the lower court’s finding that Wofy’s use “aligned with criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching . . . , scholarship, or research,” and instead construed the use in the most simplistic terms: “The ‘use’ at issue is . . . the reproduction of copyrighted photographs in a book offered for sale.” So, the Ninth Circuit said, the use was both commercial and non-transformative.

That kind of superficial analysis of the purpose and character of Wofsy’s use is not sufficient in fair use analysis. While it is true that Wofsy copied the photographs for use in a book offered for sale, at that high level of abstraction, virtually any unauthorized use of images in a book offered for sale would fail this version of the factor one analysis. Such an approach would radically alter commonly accepted understandings of how fair use applies to nonfiction publishing and would upend the market, which relies heavily on fair use to incorporate images in “books offered sale.”

As the Supreme Court recently stated, “in determining whether a use is ‘transformative,’ [a court] must go further and examine the copying’s more specifically described ‘purpose[s]’ and ‘character.” In this case, Wofsy’s purpose in using the images was to create a “systematic and comprehensive illustrated record of Picasso’s paintings,” far more complete than the Zervos Catalogue and with substantial reference information on with substantial cross-reference information to aid scholars in finding other catalogs that include each image, and where each underlying original Picasso may be found. These uses are new and different from the original photographs, enabling scholarship and research, and making them consistent with the Copyright Act’s prototypical examples of fair uses. Had the court interrogated the purpose and character of Wofsy’s use more thoroughly, it would have reached the same conclusion as the district court and found this factor too weighed in favor of fair use.

What comes next?

Given the importance of fair use and free speech to U.S. public policy, and these significant errors in the Ninth Circuit’s decision, last week, Wofsy filed a petition with the Ninth Circuit for rehearing and rehearing en banc. Authors Alliance intends to submit a brief supporting their petition, which we hope will help the court address these errors.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.