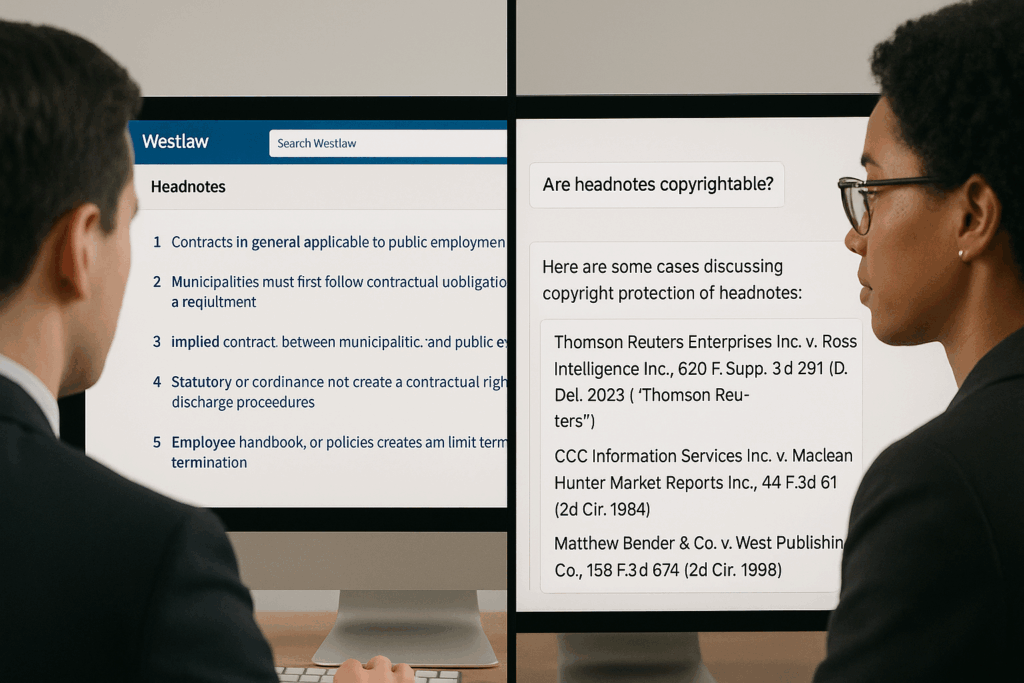

Two attorneys, one using Westlaw and Headnotes, the other prompting an AI legal tool. Images are meant to be broadly illustrative and are not intended to be accurate in every detail.

Yesterday Authors Alliance filed an amicus brief in Thomson Reuters v. ROSS Intelligence, the long-running lawsuit between Thomson Reuters, owner of Westlaw (a legal research platform) and ROSS Intelligence, an AI-powered start up legal research platform.

The suit is about ROSS’s use of Thomson Reuters’ Headnotes (concise summaries of legal points within cases) to create training data for its own AI-driven legal research platform. While no headnotes were reproduced in the ROSS system outputs, Thomson Reuters sued based on ROSS’s access and use of the headnotes in the intermediate step of training its system.

Though the suit is different in many ways from other generative AI lawsuits winding their way through the courts, this one is significant because it is the first time a US Circuit Court will have the opportunity to directly address the applicability of fair use to AI training. We published a post back in February explaining the lower court’s decision, of which we are quite critical on several key points.

ROSS filed its opening brief a week ago, raising two principal arguments:

1) that the headnotes at issue are not original, since they are derived from and dedicated by the underlying court decision from which they come, and therefore are not protectable by copyright, and,

2) Even if the headnotes are protected by copyright, ROSS’s use was a fair use.

Authors Alliance’s Brief

Our brief focused on two subsets of those issues, under fair use. This is the summary of our argument:

This case raises fundamental questions about the scope of fair use that extend far beyond AI training or the technology directly before the court. We agree with ROSS and the other amici in support of ROSS that AI training—including of the kind presented in this case—should be considered fair use. Our brief aims to help the court understand why the district court erred on two specific facets of the fair use analysis and why, if the district court’s view is adopted by this court, it would threaten a wide variety of long-accepted transformative fair uses engaged in by creators, students, and researchers.

First, under the first fair use factor, assessing the “purpose and character of the use,” the district court wrongly conflated competing users with competing uses. ROSS and Thomson Reuters both provide competing legal research services; that is true. But the issue before the district court was not about copyright in the entirety of the Thomson Reuters legal research service, or Westlaw, or even the KeyNumber system. The District Court segmented all other claims and chose to focus solely on the copyright claims in headnotes—short factual summaries of public domain cases. ROSS did not use those headnotes to publish competing headnotes, or in any other way substitute for Thomson Reuters’ expressive content. Instead, ROSS made intermediate copies of the headnotes to extract statistical relationships for its training algorithm—a highly transformative use that serves an entirely distinct purpose from the original headnotes. The court’s narrow interpretation of intermediate copying—limiting it only to computer code cases where copying is necessary—contradicts decades of precedent recognizing that non-public copying for the purpose of accessing unprotectable elements strongly favors fair use across a wide range of uses.

The district court’s flawed reasoning, if adopted by this Court, could inhibit countless legitimate activities long protected by fair use, such as artists studying famous paintings through sketching; students translating passages for language practice; and researchers copying materials to extract and report on factual information or engage in scholarly analysis. These uses, like ROSS’s training of its algorithm, involve copying for distinct purposes that serve the public interest without substituting for the original work’s market.

Second, under the fourth factor, the court improperly focused on speculative markets rather than actual markets Thomson Reuters had exploited or was likely to exploit for its headnotes. Copyright law does not grant rightsholders control over transformative markets just because they express a desire to license works for those purposes. To do so would collapse the fourth factor inquiry, leading courts to find market harm in any instance where a copyright holder makes a bare allegation that it had a desire to license their works for the subject use.

ROSS’s use serves compelling public interests by increasing access to legal information through innovative research tools, while its outputs consist entirely of public domain judicial opinions that cannot substitute for Westlaw’s proprietary content. Properly applied, both the first and fourth factors strongly support fair use. This Court should preserve the vitality of fair use for all creators, researchers, and innovators and reverse the district court’s contrary ruling.

Other Amicus Briefs Filed

A significant number of additional amicus briefs were filed in support of ROSS. If you are interested in exploring them in greater detail, we have provided links to each of them below:

Brief on behalf of Electronic Frontier Foundation, American Library Association, Association of Research Libraries, Internet Archive, Public Knowledge, and Public.Resource.org (brief argues that individual Westlaw headnotes are unlikely to satisfy copyright’s originality requirement; even if copyrightable, the thinness of the copyright should weigh heavily in favor of fair use under the second factor).

Brief on behalf of Computer & Communications Industry Association, Chamber of Progress, and NetChoice (brief focuses on errors in the district court’s first and fourth factor analysis – “With respect to the first factor, however, instead of considering the purpose and character of ROSS’s use of copied material, the district court considered the purpose and character of ROSS’s legal search engine.” “Because here the “copyrighted work” referenced in the fourth factor was the headnotes, the district court should have considered the harm to the market for the copied headnotes.”).

Brief on behalf of Copyright Law Professors (Edward Lee, Matthew Sag, Pamela Samuelson, Christopher Jon Sprigman, Rebecca Tushnet) (“ROSS’s tool provides a public benefit of the highest order in our democracy by fostering an informed citizenry with greater accessibility to judicial opinions. ROSS’s nonexpressive, highly transformative use is a fair use.”).

Brief on behalf of Randy Goebel and Larry Ullman (This brief works to provide additional context for the technology underlying ROSS’s system.).

Brief on behalf of Next Generation Legal Research and Technology Platforms Cicerai Corp., Dispute Resolution AI, Free Law Project, Juristai Legal Technology Group Inc., Paxton AI, Inc., and Trellis Research, Inc. (This brief provides a thorough take down of the district court’s copyrightability and fair use analysis. “The sculpture analogy, however, crumbles upon closer inspection. Its most fundamental flaw is the notion that a court opinion is somehow equivalent to an untouched, blank block of marble. Not so. The more accurate analogy is that a judicial opinion is the final product of a judge taking a block of marble and carefully, skillfully chiseling away the surrounding mass to create a host of precise details, each of which reveal a specific point of law or fact.”)

Brief for Brian L. Frye, Jess Miers, and Mateusz Blaszczyk (brief similarly argues that headnotes are not copyrightable; it also takes aim at market dilution theory, which featured prominently in Kadrey v. Meta.)

Brief on behalf of Heather Meeker, Technology Law Partners (brief argues that headnotes are not copyrightable, “Headnotes are generally little more than paraphrasing of the language of a court’s decision. The better written a headnote is, the more factual it is.”)

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Copyright News and Articles - Copyrightlaws.com: Copyright courses and education in plain English