Under US copyright law, authors have one right that is emphatically inalienable: the right to terminate 35 years after a copyright grant. Unless a work is made for hire under §201(b), the work will be subject to termination.

A recent decision from the Southern District of New York, however, construed the termination right so narrowly that—if upheld by higher courts—would leave authors with very little to terminate.

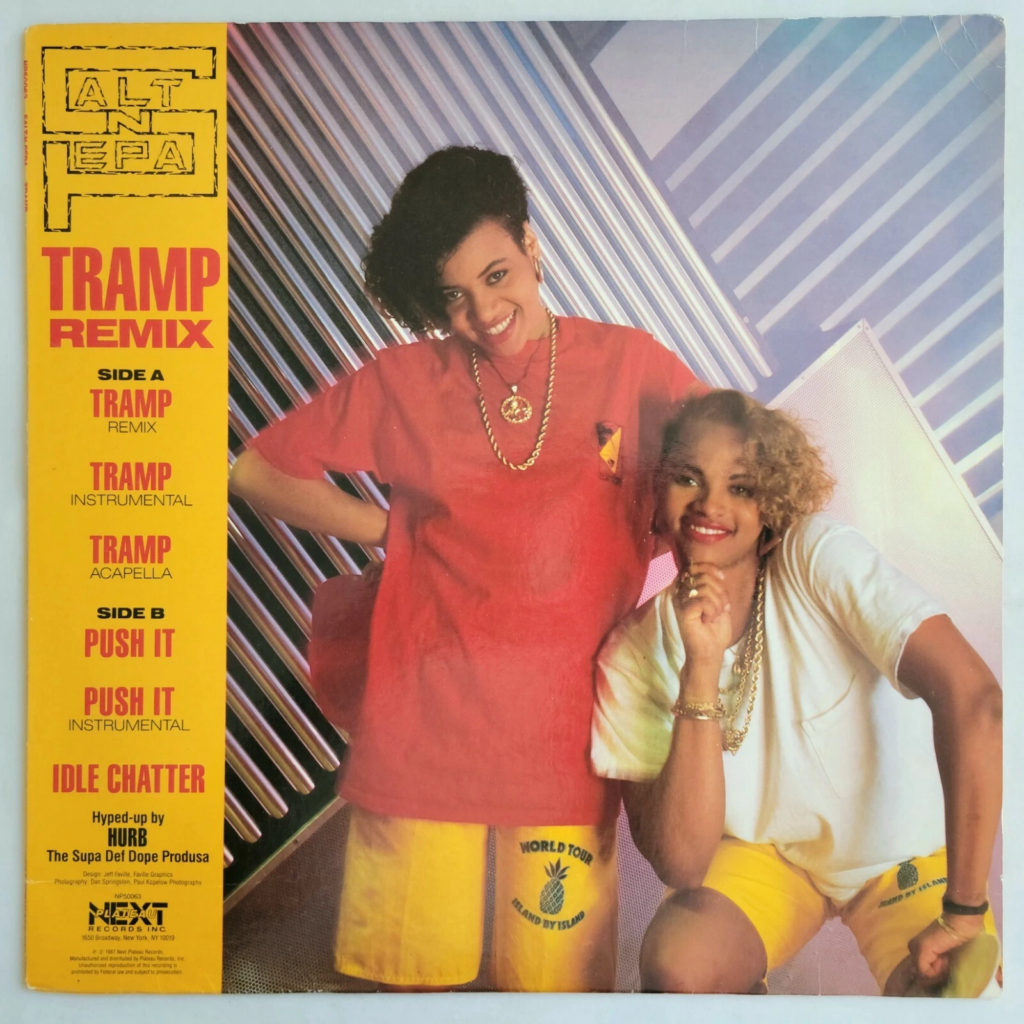

Making Sense of Cheryl James & Sandra Denton (aka Salt-N-Pepa) v. UMG Recordings

On January 8, Judge Denise Cote of the Southern District of New York dismissed the hiphop group Salt-N-Pepa’s request for declaratory relief, holding that the plaintiffs cannot exercise any §203 termination right against the defendant, UMG. The facts of the case are straightforward:

Cheryl James and Sandra Denton (“Salt” and “Pepa” respectively) had an agreement with a production company in 1986 that referred to the company as “the sole and exclusive owner of any and all rights” in Salt-N-Pepa recordings. The company then assigned those rights to the predecessor company of UMG. It is undisputed by the parties that UMG is the current copyright holder of the Salt-N-Pepa recordings at issue, and that Salt-N-Pepa served timely notice purporting to terminate UMG’s rights. The parties disagree on whether the recordings are works made for hire and thus exempted from termination under §203, or if Salt-N-Pepa may exercise their §203 termination right.

Spoiler alert—the judge declined to opine on this disputed issue: “this Opinion does not reach the issue of whether the recordings were, in fact, works made for hire.”

Despite this refusal to address the central question of the case, the court’s untethered opinion focused largely on an analysis of the contracts relevant parties have signed, and this led the court to conclusorily assert that Salt-N-Pepa were never the copyright owners of the recordings they sought to terminate.

But termination right does not depend on copyright ownership. This alone renders the court’s lengthy ownership analysis irrelevant. Under §201(a), “[c]opyright in a work protected under this title vests initially in the author or authors of the work.” Authors are always the initial copyright owners of their works—the only exception being a work made for hire under §201(b) where an employer or commissioner is deemed the legal author of a work.

In an exceedingly unique turn of reasoning, the court never got to the question of whether the recordings were works made for hire or if Salt-N-Pepa were legal authors to the recordings. The court’s ultimate holding hinged entirely on a single phrase in §203(a), which mentions transfers “executed by the author” as a part of “condition for termination.” According to the court:

the statutory text in § 203 is clear: Plaintiffs can only terminate copyright transfers that they executed. They cannot terminate a copyright grant executed by [the producers]. As a result, Plaintiffs do not plausibly allege a claim for declaratory relief.

Because in the court’s eyes the relevant transfer agreements were executed by Salt-N-Pepa’s former producers, the court deemed termination against the defendant impossible. This interpretation, however, directly conflicts with the statute as a whole. §203(a)(4), for example, expressly subjects “the grantee or the grantee’s successors in title” to termination.

If we were to accept this court’s novel theory, a publisher or distributor could easily defeat any author’s termination requests simply by interposing a new entity, ensuring that the author is neither a party to, nor an executor of, the new grant.

What Went Wrong?

Judge Cote dismissed Salt-N-Pepa’s claims at the pleadings stage, despite the fact that Salt-N-Pepa selected a valid termination effective date and provided timely notice within the prescribed statutory window according to allegations in the complaint.

When ruling on a defendant’s motion to dismiss, the court is required to assume all of the factual allegations made by the plaintiffs as true and to interpret everything in a way most favorable to plaintiffs. To survive a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, plaintiffs only need to make “plausible” claims in their complaint.

The plausible claim Salt-N-Pepa made was that they are the authors of the recordings and therefore entitled to exercise their §203 termination rights.

The court admitted at first that §203 would not apply to the Salt-N-Pepa recordings only if they were works made for hire. Yet without determining, as a matter of law, whether the Salt-N-Pepa recordings at issue were works made for hire under §201(b), the judge shifted gear to hyperfocus on a single phrase in §203(a): “executed by the author” as “condition for termination.” She concluded—somehow without thinking to look beyond that one phrase—that “[p]laintiffs can only terminate copyright transfers that they executed.”

No one disputes that §203 applies only to grants executed by authors; that limitation is in the plain text of §203(a). But §203 places no limitation on who may be affected by authors’ exercise of their termination rights; those rights are not only valid against parties to the agreements personally signed by authors. To the contrary, §203 expressly provides that termination may be asserted against “the grantee or the grantee’s successors in title,” whose interests in an author’s work can be terminated per §203(a)(4) and 203(b)(4):

The termination shall be effected by serving an advance notice in writing, signed by the number and proportion of owners of termination interests required under clauses (1) and (2) of this subsection, or by their duly authorized agents, upon the grantee or the grantee’s successor in title. §203(a)(4)

A further grant, or agreement to make a further grant, of any right covered by a terminated grant is valid only if it is made after the effective date of the termination. As an exception, however, an agreement for such a further grant may be made between the persons provided by clause (3) of this subsection and the original grantee or such grantee’s successor in title, after the notice of termination has been served as provided by clause (4) of subsection (a). §203(b)(4)

As is made clear by the plain text in §203(a)(4) and (b)(4), Congress did not choose the “executed by the author”language in §203(a) to restrict an author’s ability to terminate transfers against parties who later acquire ownership through a chain of assignments. Properly understood, the “executed by the author” language serves an entirely different function: it excludes authors’ heirs from exercising termination rights for grants the heirs executed.

This is evident when §203(a) is compared with §304(c)(1) and (d). Unlike §203, §304 extends termination rights to both grants executed by authors and their heirs. This difference between §203 and §304 arose out of a matter of timing: when the 1976 Act went into effect on January 1, 1978, some authors’ heirs had already assigned the authors’ copyrights and would have been unfairly disadvantaged by the 1976 Act absent a corresponding termination right; whereas §203 applies only to post-1/1/1978 grants, where parties would be on notice that heirs do not possess termination rights for transfers they themselves execute.

Congressional intent is crystal clear on this point as well:

However, although affirmative action is needed to effect a termination, the right to take this action cannot be waived in advance or contracted away. Under section 203(a) the right of termination would apply only to transfers and licenses executed after the effective date of the new statute, and would have no retroactive effect. The right of termination would be confined to inter vivos transfers or licenses executed by the author, and would not apply to transfers by the author’s successors in interest or to the author’s own bequests.

Put simply, §203(a)’s “executed by author” language functions to prevent heirs from transferring a copyright only to later exercise a termination right that they do not hold under the statute.

Authors’ Inalienable Right to Terminate

The policy of giving authors an opportunity to renegotiate prior copyright transfers long predates §203. Lawmakers have long recognized the unfortunate reality that authors often entered into unremunerative agreements at the outset of a work’s commercial life. (e.g., Superman’s creators assigned their copyright for $130). This ethos can be traced back to the first Copyright Act of 1790 where Congress gave the right to a renewal term exclusively to authors.

A century later, the final House Report on the 1909 Act again championed for the protection of the author’s interest in a work’s unforeseen—and unforeseeable—commercial success:

If the work proves to be a great success and lives beyond the term of twenty eight years your committee felt that it should be the exclusive right of the author to take the renewal term, and the law should be framed as is the existing law, so that he could not be deprived of that right.

Unfortunately for authors at the time, this Congressional intent did not end up being adequately captured in the plain text of the 1909 Act; the statute did not expressly state whether an author could assign his renewal interest during the initial copyright term. Lacking clear guidance from the statute, the Supreme Court looked to English case law for guidance, and in its 1943 landmark decision in Fred Fisher Music Co. v. M. Witmark & Sons, found authors’ rights to renewal terms assignable. Criticism of the decision ensued; but lower courts had no choice but to follow the Supreme Court precedent.

Addressing the judiciary’s failure to make renewal terms inalienable for authors during the initial copyright term, the final Register of Copyright’s Report in 1961 in preparation for the revision of the 1909 Act again emphasized the underlying policy concerns:

The courts have held that an assignment of future renewal rights by the author is binding if he lives into the 28th year and renewal registration is then made in his name. In that situation the author’s renewal rights become the property of the assignee as soon as the renewal term begins. It has become a common practice for publishers and others to take advance assignments of future renewal rights. Thus the reversionary purpose of the renewal provision has been thwarted to a considerable extent.

Contrary to the Witmark majority’s assertion that preserving an author’s opportunity to renegotiate a copyright grant rests on the premise that authors are “congenitally irresponsible” and “they are so sorely pressed for funds that they are willing to sell their work for a mere pittance,” the justification for termination is better understood as an imbalance in negotiation power and the inherent unpredictability of a work’s future value. Even the most “responsible” authors likely cannot predict the true value of their works, nor can they—particularly at the beginning of their careers—bargain for the fairest deals against an established publisher or distributor. As the final House Report on the 1976 Act states:

The provisions of section 203 are based on the premise that the reversionary provisions of the present section on copyright renewal (17 U.S.C. sec. 24) should be eliminated, and that the proposed law should substitute for them a provision safeguarding authors against unremunerative transfers. A provision of this sort is needed because of the unequal bargaining position of authors, resulting in part from the impossibility of determining a work’s value until it has been exploited. Section 203 reflects a practical compromise that will further the objectives of the copyright law while recognizing the problems and legitimate needs of all interests involved.

§203 of the 1976 Act finally gave all future authors the statutory, inalienable right to terminate any copyright transfers executed after January 1, 1978. (Whereas §304 gave termination right to those grants executed prior to 1978). Anyone wishing to exercise the termination right can do so by sending proper notice to “each grantee whose rights are being terminated, or the grantee’s successor in title.” The effective date of termination must be within a five-year period described in section 203(a)(3), and authors have a thirteen-year window to serve the notice and reacquire their copyrights per 203(a)(3)(A).

Conclusion

Where both the Congress and the Supreme Court have spoken clearly, the author’s right to terminate copyright transfers must remain inalienable. The purpose of the termination right has always been to “help authors, not publishers or broadcasters or others who benefit from the work of authors.”

Judge Cote’s decision is clearly a mistake. What is most striking is how readily the judge embraced an argument that, if followed, would render evading an author’s termination rights trivially easy. While the plaintiffs have indicated their intent to appeal, the more efficient course may be for the court to reconsider its order.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.