The following guest post by Paul Heald describes his recent analysis of the beneficial effect of rights reversion and termination of transfer in the traditional and ebook markets. Heald is the Richard W. and Marie L. Corman Professor of Law at the University of Illinois. He is also a fellow and associated researcher at CREATe, the RCUK Centre for Copyright and New Business Models in the Creative Economy, based at the University of Glasgow. His recent publications have focused on economic aspects of the public domain, patents, studies of best-selling fiction and musical compositions, and the behavior of famous trademarks in product and service markets. In addition to his scholarly work, Heald has published three novels.

The following guest post by Paul Heald describes his recent analysis of the beneficial effect of rights reversion and termination of transfer in the traditional and ebook markets. Heald is the Richard W. and Marie L. Corman Professor of Law at the University of Illinois. He is also a fellow and associated researcher at CREATe, the RCUK Centre for Copyright and New Business Models in the Creative Economy, based at the University of Glasgow. His recent publications have focused on economic aspects of the public domain, patents, studies of best-selling fiction and musical compositions, and the behavior of famous trademarks in product and service markets. In addition to his scholarly work, Heald has published three novels.

Authors Alliance has been encouraging authors to recapture their copyrights in order to “free up” their works for new uses and wider distributions, either with new publishers or through online postings under Creative Commons licenses. Authors do benefit from rights reversions, but a recent empirical study, “Copyright Reversion to Authors (and the Rosetta Effect): An Empirical Study of Reappearing Books” shows that consumers of books are likely to experience a significant benefit from author rights reclaimings as well.

In my sample of 1,909 book titles, between 20-23% appear to be in print only because of rights reversion.

Here’s a reminder of the four ways that authors who have assigned their rights to a publisher can get back their copyrights:

1) Ask the publisher nicely (always an option, and for help with this, see the Authors Alliance guide to rights reversions);

2) File a notice to terminate an author’s prior transfer of rights under section 304 of the Copyright Act (a right which arises 56 or 75 years after publication for a work first published between 1923-77);

3) File a notice to terminate an author’s prior transfer of rights under section 203 of the Copyright Act (a right which arises 35 years after the transfer of a work first published after Jan 1, 1978) (for help with this, see the Authors Alliance/Creative Commons Termination of Transfer Tool at rightsback.org);

4) Exploit a key limit on grants under pre-digital era publishing contracts that did not effectively assign ebooks rights (a contract that merely assigns all rights to a work “in book form” does not effectively transfer ebook rights).

Authorial assertion of ebook rights under this fourth option is known as the Rosetta Effect, after a famous case which worked a surprise de facto “reversion” of ebooks rights to authors in 2002.

My study was undertaken to test the claim that a change in the ownership of copyright in a work from original publisher back to an author (or her estate) might lead to the better dissemination of out-of-print or otherwise commercially inactive works. The study focused on the availability of more than 1,909 new editions of books that had been at one time New York Times (NYT) bestsellers, titles by NYT bestselling authors (whether the book was a bestseller or not), and books reviewed in the NYT Book Review.

A close analysis of the identity of current publishers of older titles shows that the recapture of author copyrights through the termination rights of sections 203 and 304, along with author retention of ebook rights under Random House v. Rosetta Books (2002), have significantly increased the availability of book titles to consumers.

The data reveal a market for reverted books that is exploited by independent publishers. The most active, Open Road Media, describes its business model on its web site: “We are committed to bringing back the backlist, making reverted titles and works that have never been converted to digital format widely available as ebooks….This program is for authors whose rights have reverted, whose titles have not previously been digitized, or who are looking to have their works available as ebooks.”

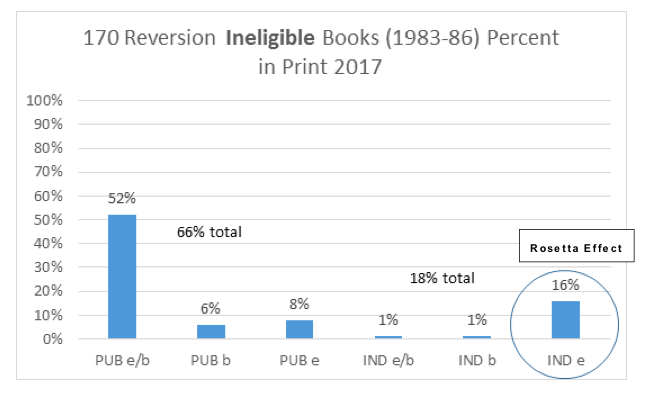

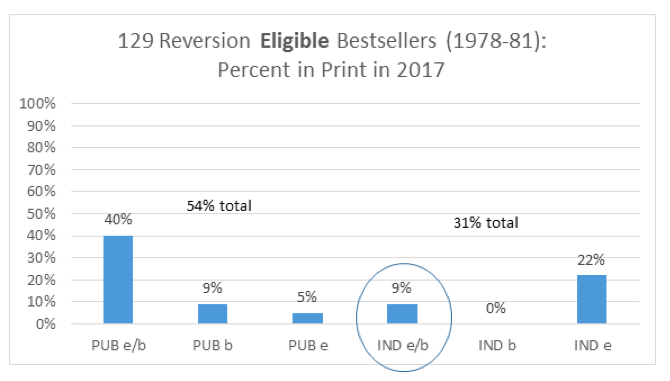

One can see Rosetta at work in the first chart below and the effect of section 203 in the second chart. Both charts list the publishers of ebooks (“e”), bound volumes (“b”), and both ebook and bound versions of a title (“e/b”). Original publishers, almost all well-known traditional publishers, are denominated PUB, while new independent publishers like Open Road, are denominated IND.

None of the bestsellers in the chart above are yet eligible for termination, so in theory, all of the copyrights are still controlled by the original publishers, who seem only interested in keeping approximately 66% of the titles in print (other sub-samples of older bestsellers show original publishers keeping as few as 12% of titles in print).

What explains the 18% additional titles offered by new independent publishers? The 16% of titles available only as ebooks are most likely due to the holding in Rosetta which gave many (but hardly all) authors the chance to control digital (but not bound) versions of their works. Beneficiaries of the ruling can partner with a new, sometimes digital-only press, to make their works available.

A look at reversion eligible books from the same era tells an additional story about the effects on availability based on section 203 termination rights:

All the works are termination eligible, but original publishers have decided to exploit about half of their older titles. (What author says “no” when Random House asks to make her out-of-print bestseller available in a new edition?) One sees reversion at work in the 9% of books offered by new independent publishers in both ebook and bound versions. The 22% available as ebooks only would seem to be in print as a result of Rosetta or of the termination threat of section 203. It’s hard to know which. But in any event, the good news is that more books are becoming more available through authorial reclaiming of rights and making new arrangements to publish them (a whopping 31% in this sample!)

The full paper, which is available here, analyzes a number of different data sets and provides an appendix of rights reversion schemes around the world. The paper also notes that few authors bother making a formal termination filing with the U.S. Copyright Office (they should!). The sending of a termination notice to a publisher, or the looming likelihood of termination, seems to be enough to create this new market being exploited by independent publishers. The story in the U.S. seems fairly clear: Rosetta and the availability of termination under section 203 and 304 are helping bring older works back into print. It is less easy to track individual author rights reversions through asking publishers for rights, but the experiences of numerous Authors Alliance members in reclaiming copyrights in this manner suggest that this option should be more widely used and recognized.

Discover more from Authors Alliance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.